Next Stop: Tennessee

After four

generations in Virginia, John Gilliam (1745-1825) begins the family migration south and

west to Tennessee.

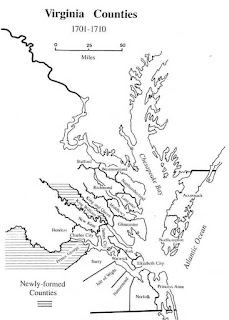

Like the three

generations of Gilliams before him, John was born in the James River Basin of

Colonial Virginia. The specific location of his 1745 birth was Albemarle

Parish, a part of Surry County. In 1754, Surry County was subdivided, and

Albemarle Parish became part of adjacent Sussex County. This explains why some

genealogists list John’s birthplace as Surry County, some as Sussex County.

John’s first eight

children (in order, John Jr., Avery, Nancy, Temperance, Frances, Hinchea, Mary

(“Polly”) and Thomas) all appear to have been born in Albemarle Parish, Sussex

County. The youngest of the children born in Sussex County, Thomas, was born in

1780, our best proof that John remained in Sussex County through 1780.

John obtained a 250-acre land grant from the state of North Carolina in Hawkins County in 1791. It is possible he left Virginia and settled the land before 1791. At least part of the reason for North Carolina issuing grants in 1791 was to preserve prior land claims before Hawkins County would become part of Tennessee (when Tennessee became a state) in 1796. John’s youngest son, Lemuel, was born in Hawkins County in 1791.

It is possible that John was preceded in the move to Tennessee by his daughters Nancy and Polly, both of whom married into the Turney family. The Turneys became one of the most prominent families in early Tennessee, settling the interior of the state in and around Smith and DeKalb counties. Peter Turney, one of Nancy's and Polly's nephews, would later become governor of Tennessee.

John obtained a 250-acre land grant from the state of North Carolina in Hawkins County in 1791. It is possible he left Virginia and settled the land before 1791. At least part of the reason for North Carolina issuing grants in 1791 was to preserve prior land claims before Hawkins County would become part of Tennessee (when Tennessee became a state) in 1796. John’s youngest son, Lemuel, was born in Hawkins County in 1791.

It is possible that John was preceded in the move to Tennessee by his daughters Nancy and Polly, both of whom married into the Turney family. The Turneys became one of the most prominent families in early Tennessee, settling the interior of the state in and around Smith and DeKalb counties. Peter Turney, one of Nancy's and Polly's nephews, would later become governor of Tennessee.

Hawkins County, where John initially settled, is

located in the Clinch Mountains in what is now the northeast corner of

Tennessee, on the border with Virginia. With a little bit of sleuthing, we can

get a close approximation of the location of the tract John received from North

Carolina. The land grant states:

“Two hundred fifty acres of land lying in our County of Hawkins in a Caney Valley on the waters of Big Creek, a branch of the Holson River beginning at two Buckeyes on Mordecai Hagood’s line thence along said line due west two hundred and twenty poles to a poplar and beech thence due south one hundred and eighty-one poles to a white oak and dogwood thence due east two hundred and twenty poles to a stake thence due north one hundred eighty-one poles to the first station, dated 26 December 1791.”

“Two hundred fifty acres of land lying in our County of Hawkins in a Caney Valley on the waters of Big Creek, a branch of the Holson River beginning at two Buckeyes on Mordecai Hagood’s line thence along said line due west two hundred and twenty poles to a poplar and beech thence due south one hundred and eighty-one poles to a white oak and dogwood thence due east two hundred and twenty poles to a stake thence due north one hundred eighty-one poles to the first station, dated 26 December 1791.”

Who was John’s

neighbor, Mordecai Hagood? According to Goodspeed’s

History of Tennessee, 1887, Mordecai Haygood was among the earliest settlers

of Hawkins County, arriving there prior to 1783. Goodspeed's states Mordecai lived about eight miles above what is now Rogersville, Tennessee. With Goodspeed's description of Mordecai’s location above Rogersville, and the land grant description that John’s

land was on Big Creek in Caney Valley, we can surmise that John’s land grant

was within the area shown in the map below.

The pioneer cemeteries identified in the map as "Gilley" and "Gillenwater" may provide some clues as to the general location of John's Hawkins County property. Both of those surnames are occasionally confused with Gilliam and may be an indication that a Gilliam created those cemeteries. John's daughter Temperance married Philip Klepper. There is also a Klepper Cemetery nearby on the map. findagrave.com lists some Gilliams from later generations as being buried there.

We know that John stayed in Hawkins County through 1795 based upon the diary entry of his brother-in-law, David Barrow. Barrow was a relatively famous Baptist preacher, married to John’s sister Sarah. His diary has been published in A Few Early Families in America, by Grace Barrow (1941). Barrow's diary entry from August 5, 1795, states he spent a day or two with John (and John's daughter Nancy and her husband, Jacob Turney) while on his way to and through Sullivan County, Tennessee, adjacent to Hawkins County.

We know that John stayed in Hawkins County through 1795 based upon the diary entry of his brother-in-law, David Barrow. Barrow was a relatively famous Baptist preacher, married to John’s sister Sarah. His diary has been published in A Few Early Families in America, by Grace Barrow (1941). Barrow's diary entry from August 5, 1795, states he spent a day or two with John (and John's daughter Nancy and her husband, Jacob Turney) while on his way to and through Sullivan County, Tennessee, adjacent to Hawkins County.

Thanks to an 1814 ruling in a lawsuit filed against John by a neighbor, Daniel Morris, we can pinpoint that John

continued to live with his family in Hawkins County until February, 1807. We

think John’s wife, Mary, may have died in 1803, and perhaps her death

precipitated John's move to Franklin County, Tennessee a few years later.

The lawsuit concerned the ownership of 57 acres in Franklin County. According to the ruling in the suit (the ruling can be found in Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Errors and Appeals of the State of Tennessee: From the Year 1816 to 1817, John Haywood, Heiskell & Brown, 1818), John had visited the property in Franklin County in February, 1806, and staked his claim to a tract of land by carving his initials into a tree. He left his son, John Jr. and his son-in-law, John DeLoach (husband of his daughter, Frances) on the site to build a cabin. John Jr., in doing so, "used" some of Morris’ logs when the neighbor was absent. When Morris returned, he claimed the property and moved into the cabin with John Jr. Reading between the lines, the two men subsequently got into a fight and Morris “was compelled by the superior force of John Jr.” to move off the property. John’s son Lemuel worked the ground that 1806 season and produced a crop. John moved the family there in February, 1807. Ultimately, the court case went against John for the portion of the land claimed by Daniel Morris, but the case does confirm that John and family moved to Franklin County, Tennessee in 1807. Tennessee tax records confirm that he and son Thomas both owned land in Franklin County in 1811-12.

The lawsuit concerned the ownership of 57 acres in Franklin County. According to the ruling in the suit (the ruling can be found in Reports of Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Court of Errors and Appeals of the State of Tennessee: From the Year 1816 to 1817, John Haywood, Heiskell & Brown, 1818), John had visited the property in Franklin County in February, 1806, and staked his claim to a tract of land by carving his initials into a tree. He left his son, John Jr. and his son-in-law, John DeLoach (husband of his daughter, Frances) on the site to build a cabin. John Jr., in doing so, "used" some of Morris’ logs when the neighbor was absent. When Morris returned, he claimed the property and moved into the cabin with John Jr. Reading between the lines, the two men subsequently got into a fight and Morris “was compelled by the superior force of John Jr.” to move off the property. John’s son Lemuel worked the ground that 1806 season and produced a crop. John moved the family there in February, 1807. Ultimately, the court case went against John for the portion of the land claimed by Daniel Morris, but the case does confirm that John and family moved to Franklin County, Tennessee in 1807. Tennessee tax records confirm that he and son Thomas both owned land in Franklin County in 1811-12.

On January 6, 1825, The State of Tennessee issued a land grant to John for an additional tract of land. Interestingly, the grant mentions the initials John had carved into a tree back in 1806:

“There is granted by the State of Tennessee unto John Gilliam…a certain tract of or parcel of land containing twenty acres…lying in the second district in Franklin County, on the waters of Beans Creek, a branch of the Elk River and bounded as follows to wit, beginning at a beech lettered “J.G.” standing in the cove of the mountain about a mile above John Gilliam’s thence south forty-eight poles to a Spanish Oak, thence west ninety-three and five tenths poles to an ash, thence north 48 poles to a black ash, thence east ninety-three and five tenths poles to the beginning.”

These records can be found in the compilation Land Grants on Elk River in Tennessee, North Carolina & Tennessee Land Grants 1783-1831, by Jack Masters, (Warrioto Press, 2016). As part of that book, Masters has located the property boundaries on modern topographic maps. With his permission, we can show a reprint of the map that shows the exact location of John's properties:

“There is granted by the State of Tennessee unto John Gilliam…a certain tract of or parcel of land containing twenty acres…lying in the second district in Franklin County, on the waters of Beans Creek, a branch of the Elk River and bounded as follows to wit, beginning at a beech lettered “J.G.” standing in the cove of the mountain about a mile above John Gilliam’s thence south forty-eight poles to a Spanish Oak, thence west ninety-three and five tenths poles to an ash, thence north 48 poles to a black ash, thence east ninety-three and five tenths poles to the beginning.”

These records can be found in the compilation Land Grants on Elk River in Tennessee, North Carolina & Tennessee Land Grants 1783-1831, by Jack Masters, (Warrioto Press, 2016). As part of that book, Masters has located the property boundaries on modern topographic maps. With his permission, we can show a reprint of the map that shows the exact location of John's properties:

The map shows how the original land grants to John and Daniel Morris overlapped, creating the dispute that was resolved in court. If the reader is interested in a personal copy of the Masters book or maps, they can be order through his website: www.cumberlandpioneers.com

John’s health may

have been declining about the time he obtained the second grant, as he drafted and dated his will on August

17, 1825. He directed that his farmland and implements be sold and the

proceeds be split among his heirs. However, he directed that a portion of his farm be set aside to create a cemetery. His son Thomas had died in 1822

and he was buried on John’s farm. The will codicil states:

“that twenty-five yards square be laid off and reserved for a burying yard on the tract of Land heretofore disposed of by me in my former will to be laid off near a walnut tree including Thomas Gilliam's grave.”

“that twenty-five yards square be laid off and reserved for a burying yard on the tract of Land heretofore disposed of by me in my former will to be laid off near a walnut tree including Thomas Gilliam's grave.”

After his death, perhaps as late as December 7, 1826, John’s will was probated

in Franklin County. Ten years after John's death, in

1836, Tennessee created Coffee County from portions of Franklin County and two

other counties. As a result of the redistricting, John’s property is located in what is now Coffee

County. We think he is buried in the Gilliam Farm Cemetery in Coffee County, the cemetery created in his will.

Other genealogists

have been able to locate the Gilliam Farm Cemetery and have preserved their

discovery on findagrave.com: (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/84701558/john-gilliam).

According to the

entry there, the cemetery is in disrepair and is located in a grove of trees a

few hundred yards off the closest road, but can be found by following these directions:

From nearby Manchester, Tennessee, at the intersection of Highways 55 and 41, take 41 southeast 12.7 miles and turn left onto Stephenson Road (the lower end) 4.2 miles and bear right onto Lusk Cove Road. About 1.1 miles and the cemetery is on the left about .2 miles in a grove near the barn.

We can locate the cemetery on the map pinpoint below, just east of the town of Hillsboro, a few hundred yards away from the "Bean's Creek" mentioned in the land grant:

From nearby Manchester, Tennessee, at the intersection of Highways 55 and 41, take 41 southeast 12.7 miles and turn left onto Stephenson Road (the lower end) 4.2 miles and bear right onto Lusk Cove Road. About 1.1 miles and the cemetery is on the left about .2 miles in a grove near the barn.

We can locate the cemetery on the map pinpoint below, just east of the town of Hillsboro, a few hundred yards away from the "Bean's Creek" mentioned in the land grant:

These are the

findagrave pictures from 2008:

In the latest satellite images on Google Maps, it appears the barns have been taken down, but a small grove still exists nearby:

What happened to John's children?

John Jr. is listed as a Franklin County resident in the 1820 census, but it is unknown where he resided thereafter.

It is not known at this time where his son daughter Avery (listed as Avery Snider in his will) lived as an adult.

Daughter Nancy (Nancy Turney in his will) moved with her husband to Tennessee from Virginia.

Daughter Temperance (Temperance Klepper in his will) likely stayed in Hawkins County with her husband and children.

Daughter Frances (Frances Deloach in his will) and her husband John received a land grant within a mile of John's property. They later moved to Jefferson County, Alabama.

Son Hinchea started his family in Hawkins County and moved to Marion County, Tennessee, just southeast and adjacent to Franklin/Coffee County, Tennessee in 1832, a few years after John's death.

Daughter Mary (Polly Turney in his will) moved to Smith County, Tennessee with her husband and moved to Searcy County, northwest Arkansas, after his death. She died there in 1845.

Son Thomas died three years before John and is buried with his wife, Elizabeth, in the Gilliam Farm Cemetery.

Son Lemuel moved to Jackson County, Alabama as an adult, but returned to Marion County, Tennessee before 1850 and died there sometime after 1862.

Next, we will pick

up with John’s son Hinchea and explore the family roots in Marion County, Tennessee.

Comments

Post a Comment