The Hildreth In-Laws: The Bowens of Virginia

The Hildreth In-Laws: The Bowens of Virginia

In this post, we briefly depart from our discussion of the Hildreths and their migration across America to discuss the families that were joined with the Hildreths by the marriage of Jeffrey Hildreth and Lily Bowen in 1785. The Bowens and their related families were fierce defenders of the settlements in the New World, fighting and dying to protect their new lives.

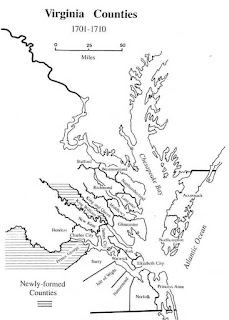

According to the chapter entitled “The Bowens of Tazewell” contained in History of Tazewell County and Southwest Virginia, 1748-1920, by William Cecil Pendleton, (link) the Bowens were Celtic Welsh. Moses and Rebecca Rees Bowen (7th great-grandparents to my generation) migrated from Wales to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania “a good many years before the Revolution.” Their son John was a Quaker and married Lily McIlhany. John and Lily McIlhany Bowen (6th great-grandparents to my generation), moved to Augusta County, Virginia (now Rockbridge County) shortly after the first settlements appeared in the Shenandoah Valley, perhaps as early as 1732. John and Lily had 12 children.

One of their five sons, Rees Bowen, married Louisa Smith. Louisa’s parents. John Smith and Margaret Harrington Smith (6th great-grandparents to my generation), also lived in Augusta (now Rockbridge) County, Va. John Smith (not to be confused with the John Smith of the Jamestown Colony), arrived from County Ulster, Ireland (now Northern Ireland) in about 1730. After his arrival in Virginia, he was commissioned an officer in the Virginia colonial militia and served under George Washington. During the French and Indian War, John commanded the stockade at Fort Vause, Virginia.

An historical marker is located where Fort Vause once stood:

With his two sons, John defended the fort against a siege by French and Indian forces. He and one son were captured (and one son was killed) when the fort capitulated on 25 June 1756. While in captivity, his son died and John was taken by the French to New Orleans and transported to France. More about the siege at Fort Vause can be found here (link).

After two years in captivity, John returned to Virginia. He offered to serve in the Revolution, but was rejected due to his advanced age.

It is believed Rees and Louisa Smith Bowen had their first home on the Roanoke River, near where the city of Roanoke, Virginia is now situated. In 1769, according to Pendleton, Rees was the second white man to bring his family to Clinch Valley, in southwest Virginia. However, according to George W. L. Bickley in History of the Settlement and Indian Wars of Tazewell County, Virginia, with a Map, Statistical Tables, and Illustrations (link), Rees arrived in 1772.

Rees scouted the location of his home and farm in the valley and named the location he selected as Maiden Spring, which can be found here:

Along with his homestead, he built a stockade-style fort as protection for his family and other settlers against Indian attacks. After he settled in the valley, his brothers John, Arthur, William, and Moses followed. One of the other settlers in the area was Daniel Boone, who occasionally took over command of the stockade when the other men were absent on military expeditions.

According to David E. Johnston, in his book A History of New Middle River Settlements and Contiguous Territory (link), Rees Bowen had quite the reputation as a prizefighter. Johnston tells of an incident where Rees and Louisa were taking a new baby to visit her family. While on horseback, they were approached by a man who challenged Rees to a fistfight, the winner of which would wear the champion’s belt. Rees tried to beg off the challenge, reminding the man that he was with his wife and child. According to Johnston, “the man would take no excuse; finally, Mrs. Bowen said to her husband: ‘Reece, give me the child and get down and slap that man’s jaws.’ Mr. Bowen alighted from his horse, took the man by the lapel of his hunting shirt, gave him a few quick heavy jerks, when the man called out to let him go, he had enough.” According to Johnston, at least one other fighter came all the way from South Carolina to challenge Rees but “came off second best.”

The Pendleton book lists a number of military expeditions to which Rees volunteered. In 1774, Rees, with his brothers William and Moses, participated in the expedition to establish the Ohio River as a boundary with Indian tribes. The expedition culminated in the Battle of Point Pleasant on October 10, 1774. A description of the military expedition can be found here: (link) According to Pendleton, brother William engaged in hand-to-hand fighting in the battle and “vanquished his savage adversary.” During the march back to Virginia, brother Moses died after contracting smallpox.

After the British Colonies declared their independence, the British army began to organize Tory militias and commenced efforts to “subjugate the rebels”. In February, 1777, the Tazewell County Court recommended that William Bowen be commissioned as a captain to lead a company of Tazewell men to fight the British forces. His commission was signed by Virginia Governor Patrick Henry (of "give me liberty or give me death!" fame) and the document remains in the family's possession. Rees was commissioned as a lieutenant under William’s command. However, at the time the company was formed and ready to march, William was sick with typhoid and Rees assumed command of the company.

A full description of the Battle of King’s Mountain can be found here: (link). On September 22, 1780 Rees’ company began its march from Wolf Creek. On the 26th, the company reached its assembly point at Sycamore Shoals three miles below present town of Elizabethton, Tennessee. On October 6, they learned that the British troops were encamped on a ridge near King’s Mountain. The company marched during the night and attacked on the afternoon of the 7th.

Pendleton provides the following account of the Tazewell company’s participation in the battle:

“The men from Tazewell were of and among these resolute mountaineers who were fighting as they were accustomed to fight the Indians; and it was upon these men that Ferguson (the British field commander) turned his best troops to make a charge with fixed bayonets.”

Lyman Copeland Draper, in King's Mountain and Its Heroes: History of the Battle of King's Mountain, October 7th, 1780, and the Events which Led to It, (link) picks up the description:

“Lieutenant Rees Bowen, who commanded one of these companies of the Virginia regiment, was observed, while marching forward to attack the enemy, to make a hazardous and unnecessary exposure of his person. Some friend kindly remonstrated with him – ‘why, Bowen, do you not take a tree—why rashly present yourself to the deliberate aim of the Provincial and Tory riflemen, concealed behind every rock and bush before you—death will inevitable follow if you persist.’ ‘Take to a tree,’ he indignantly replied, ‘No! Never shall it be said that I sought safety by hiding my person or dodging from a Briton or Tory who opposed me in the field.’”

According to Pendleton, “a few moments after uttering these words, the fearless Bowen was shot through the breast, fell to the ground, and expired almost instantly.”

Rees Bowen was buried in a mass grave on the battlefield at King’s Mountain and a marker bears his name with the other soldiers that died that day.

Rees Bowen’s service is recognized as qualifying his direct descendants for membership in the Daughters of the American Revolution (Ancestor #A012723) and Sons of the American Revolution (Patriot #118510).

Before we leave our discussion of Rees Bowen, we should pause to consider the sacrifices of his wife, Louisa Smith Bowen. As teenager, she suffered the loss of two brothers in the French and Indian War, along with the capture of her father and his absence from her life for two years. She was widowed on her 40th birthday when her husband was killed on the battlefield. She had at least five of her eight children at home when she was widowed. She never remarried and was buried after her death in 1834 in a family cemetery near their home at Maiden Spring.

Rees Bowen’s brother William would go on to command a cavalry unit during the Revolution, scouting the western frontier of North Carolina that would become Tennessee. After the revolution, he would become one of the first settlers of Tennessee and in 1813, his son, John Bowen, would be elected to Congress from Tennessee. In 1868, his grandson, William Campbell, would be elected Governor of Tennessee.

Although Rees and his brothers were active soldiers in the Revolution, two sisters remained loyal to England. His sister Rebecca married Moses Whitley and they moved to Canada in 1776. Moses became an officer in the British army and fought against the rebels. Rees’ sister, Lily, married an Episcopal minister and the two moved to England during the Revolution.

Henry Bowen, Rees’ son and brother to my generation’s 4th great-grandmother, Lily Bowen Hildreth, remained in the home in Maiden Spring. His grandson, John Warfield Johnston would serve two terms as US Senator from Virginia after the Civil War.

The home in Maiden Spring (link) remained in family hands through the 1900s and may still be home to Bowen descendants.

Comments

Post a Comment